Beech

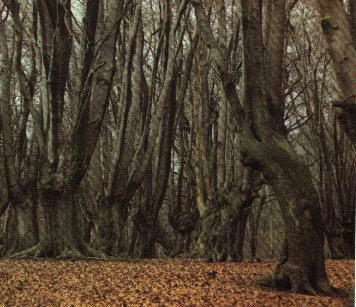

Queen Victoria is supposed to have insisted that 'coals' for the palace fires were made trom trees at Burnham Beeches, near Slough. These trees, distorted by centuries of lopping and regrowth are typical ot many old woods near London. Dozens more must have been uprooted and built over. In addition there are about 25,000 acres ot beech - tall forest, not ruined coppices - within an hour's drive from London. Their presence is mainly due to the furniture industry. The work of the chair makers was done halt in the woods, the 'sticks' being turned on open-air treadle lathes. These men and their masters were careful not to use up the wood faster than it grew.

Now their trees are tall - the last chair bodger retired a few years ago. The

National Trust protects some of the woods, others are still managed for

timber. Beech is next to oak in value and, sawn instead of split and turned, is

still a basic material of furniture - not always visibly. Much of the wood is

imported. The greatest concentration of beechwoods is on the Chiltern Hills.

The trees thrive as no other on the steep escarpment of the chalk, their long

roots exposed on the shallow soil. But they reach their most majestic heights

on the plateaux above, where the chalk is overlaid with deeper soil.

Beech is not exclusively a calcicole: it will grow on many well-drained soils.

In the northern part of Epping Forest it shares the gravelly ground with hornbeam.

At Burnham Beeches there is gravel, little chalk. There are many beech

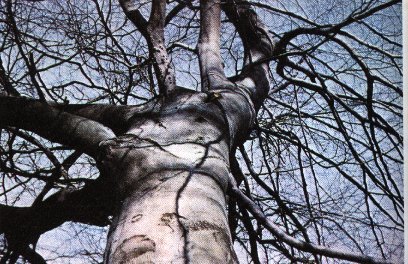

plantations all over Britain, often far from chalk or limestone. Ancient

pollard trees are a feature of old common land in the south-east, often at

lane sides where people had the right to 'fair loppings'. There are old pollard

beeches in the New Forest, on common land.

Beechwoods remain on all the downs and in the Cotswolds often as

preserved 'hangers', surrounded by sheep pasture or, more frequently now,

by smooth arable fields. There are impressive beech hedges in north

Somerset and high beechwoods near Buxton at over 1,000 feet. Lines of

beeches as shelterbelts have been planted in northern England and

Scotland: the tall trees not their usual grey, but green with algae or white

with lichens. Beeches in large plantations in the lowlands of Scotland as far

north as Aberdeen are a surprise to the Southerner.

A plantation usually has trees of noticeably similar ages, while a natural

beechwood - or any other wood - is marked by the dissimilar ages, shown by

thickness of trunk. A wood which has been left alone will also have its share

of dead trees. The high beechwoods, though they have an immemorial look

about them, have usually grown up from trees which were once regularly

cropped at an age convenient for making logs which could be cleft and

shaped for the turners. Trees of more than 200 years are said to be unusual.

Some giants were, no doubt, left as parent trees. There is no reason to

suppose that many present-day beechwoods are not on their original native

sites.

Ecologically the beech, as our tallest forest tree, forms the climax of a

natural succession described by Tansley:

'from grassland through scrub sometimes with ash; then oak, the native tree of

widest distribution and most adaptable habit.'

Beeches will grow in the shade of oaks when the soil suits them, and theme is

nothing to stop the eventual formation of a pure, tall beech forest which is

self-perpetuating. The shade is too deep for other trees to regain dominance.

Certain types of scrub - box and juniper- are directly colonised by beeches.

Natural clearings, caused by dead trees, are quickly filled by wind-seeded

annual herbs or by brambles, usually present in creeping, flowerless, form

on the beechwood floor. Seedling beeches, which start everywhere in the

dark woods but normally end as crackling twigs, here get their chance to

grow up through the plants which filled the gap; sometimes they are

accompanied by the odd yew, holly, or cherry, seeded by the birds. The

evergreens can grow easily in the surrounding shade;the cherry can

overtake the sapling beeches and reach the hundred-foot-high canopy to

take its share ofthe sunlight.

At its edge, the beechwood expands over the scrub with the help of jays,

pheasants, mice, and squirrels, until it reaches soil too heavy (or more

usually, farmland). It will gradually advance through adjacent mixed

woodland until, on less favourable soil, it fails to compete. This is the

textbook situation and you may test it in action anywhere along the

Chilterns, where a great variety of scrub (identified elsewhere in this book)

occupies the more exposed escarpments - and woodland of various types besides beech

can be found on the plateaux and the dip slopes.

At its edge, the beechwood expands over the scrub with the help of jays,

pheasants, mice, and squirrels, until it reaches soil too heavy (or more

usually, farmland). It will gradually advance through adjacent mixed

woodland until, on less favourable soil, it fails to compete. This is the

textbook situation and you may test it in action anywhere along the

Chilterns, where a great variety of scrub (identified elsewhere in this book)

occupies the more exposed escarpments - and woodland of various types besides beech

can be found on the plateaux and the dip slopes.

The early history of the beechwoods is confused and open to conjecture:

their distribution, at least in England, in the period immediately before the

Roman occupation, is almost as wide as the present planted distribution.

The massive pollen deposits of other common trees, which are preserved in

peat, are, in the case of the beech, absent, for its most favoured habitat is

the chalk. Pollen is, in any case, not over-abundant and is likely to remain

within the confines of the beechwood where gales are subdued. Theme are

widely scattered macroscopic remains.

Our present intergalacial period was well advanced, by six or eight

thousand years, beforethe beech became established in Britain. By this

time the country had been invaded by farming peoples, and no one really

knows whether the beechwoods or the farmers came first.